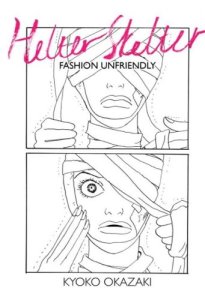

Have you ever looked at the cover of the latest fashion magazine or celebrity gossip magazine and envied the body of the featured model or actor? Have you gone to great lengths to look good, or feel bad because you don’t fit the image on the magazine? Even if you haven’t done or felt any of these things, it’s likely that someone you know has, which is what makes Kyoko Okazaki’s Helter Skelter, a josei manga about our obsession with beauty, such an unnerving read.

For a story of the hidden beastliness of the beauty culture, there’s no better protagonist than Liliko, a supermodel whose gorgeous face has all of Japan captivated. Yet behind that mask of perfect beauty lies dark secrets. Liliko smiles and titters in front of the camera, putting on an act of effortlessness, but in reality, she’s gone to the farthest lengths possible to achieve her beauty, undergoing an excruciating full-body plastic surgery in order to become gorgeous enough to make it in the modeling industry. Even so, the ticking hands of time haunt Liliko, an incessant reminder of the inevitable limit to her beauty and the interest the public has in her. After clawing her way to fame and fortune, her beauty, and the life she’s built around it, begin to unravel, and Liliko spirals further into a world of madness and violence as her desperation to stay beautiful and beloved grows.

Of all the books, manga, movies, and other fiction I’ve been exposed to, Liliko definitely ranks among the top levels of disturbed and disturbing protagonists. She attacks rivals in love and beauty, takes her hatred of herself out on others in the most twisted fashions, and in general seems the kind of unsavory character one would strive to avoid. What is perhaps most captivating about Helter Skelter is that, despite it all, Liliko’s desperation to retain her youth and beauty remains somehow understandable. Liliko exists in an amplified version of the daily pressure people experience to look, dress, and act a certain way, an industry where your worth (and income) depends entirely on your physical appeal. Low self-esteem and limited options eats at Liliko, and she relies on the image that she’s crafted to survive. It’s a job that leaves her feeling empty. In order to become the beloved Liliko, she makes herself into whatever the public desires, not just her body, but also her personality. She splits herself in two in order to present a dream Liliko to the media who manages to give the public what they want to hear without say anything at all, a pretty blank slate that reflects only fantasies. All the while she privately lets loose a personality shaped by a cruel reality.

As mangaka Okazaki suggests, however, hanging your self-worth on something as precarious as your fame as a supermodel, or more simply, your beauty, is a dangerous gamble, and one that will inevitably stop paying off. Liliko knows it, and this knowledge drives her further into a corner. She clings to a wealthy and spoiled young heir who the hardworking Liliko despises, believing that he’ll be her meal ticket when she’s too old to model. She becomes extremely antagonistic toward younger models and other women who threaten her position. And as her exterior begins to give way and all her struggling seems to be for nothing, her mental state crumbles as well. Liliko begins to wonder what her worth is when her only function is to wear clothes and pose, and tries to make herself feel better by abusing her manager, hellbent on dragging others down with her. She’s trapped, having made herself as beautiful as possible in the eyes of others yet with nowhere to go but down by the standards of society. Even her younger co-worker Kozue, the natural beauty who’s been modeling since she was a small child, cannot seem to break free of the fashion industry. Despite wanting to disappear from the public’s eye and desiring to pursue an education, she feels that her skills are limited to modeling. In one of the manga’s more surreal sections, an image of a beef cut chart slapped into one of Liliko’s dreams reiterates the sense that these women are little more than meat.

But as Helter Skelter shows, it’s not just the models trapped in a space where their worth rests on their beauty. This obsession with beauty is something that infects society as a whole. It’s interesting that the summary on Vertical’s English edition of Helter Skelter frames it as an examination of celebrity culture and the cost of fame. While it is indeed those things, Helter Skelter criticizes beauty culture, and peels back the layers to reveal a vicious cycle of body image, the media, and society. Interspersed throughout Liliko’s breakdown are scenes of faceless girls and young women preoccupied with their looks, idolizing the illusion that is Liliko as true beauty, fretting over their flaws, and strategizing how to become prettier. Liliko’s full-body plastic surgery may seem fictitious, but it’s not too far from the truth. Women use plastic surgery in an attempt to obtain the unobtainable photoshopped beauty that we see daily on glossy magazine covers and movie posters. Ugly and disturbing as it is, what the desperate Liliko reflects is our own desperation to be perceived as beautiful, as well as our fears of aging. And it’s a never-ending cycle, as Okazaki shows us. As Liliko falls, other young women take her place, seeking beauty just as frantically as Liliko.

Okazaki’s Helter Skelter is not an easy manga to read. I knew that when I purchased it, and it sat on my bookshelf for months before I finally decided to brave this twisted josei manga that rips through the sleek appearance of the fashion industry and pop culture with knife-like sharpness. Readers should note that this manga is rated mature, and for good reasons. Although it’s presented to make an intelligent point, it nevertheless features numerous disturbing scenes of sexual abuse and violence. But Okazaki’s manga Helter Skelter isn’t supposed to leave its readers feeling warm and fuzzy. This harsh, surreal reflection of reality that Okazaki has created is meant to unnerve you. If you’re looking for a thought-provoking examination of beauty, media and celebrities, and the effects these things have on the mind, look no further.